Small Cells – Not In My Front Yard!

By Tom Leddo, Vice President and Lynn Whitcher, General Counsel

“A favorite theory of mine — to wit, that no occurrence is sole and solitary, but is merely a repetition of a thing which has happened before, and perhaps often.” –Mark Twain

NIMBY

Anyone who has worked in the wireless infrastructure industry for a while has heard the term NIMBY, an acronym for Not In My Back Yard. According to Wikipedia:

“NIMBY is a pejorative characterization of opposition by residents to a proposal for a new development because it is close to them (or, in some cases, because the development involves controversial or dangerous technology) often with the connotation that such residents believe that the developments are needed in society but should be further away. The residents are often called Nimbies and their state of mind is called Nimbyism.”

In the wireless infrastructure industry, this “controversial or (perceived) dangerous technology” is a cell tower.

We first heard the term NIMBY in the late 1990’s. In 1996 the industry began to rapidly deploy the first digital networks, or what we now call 2G. Cell towers were new to most communities around the country and therefore most municipalities did not have sufficient code to deal with these new structures, nor the staff to handle the abundance of zoning and permitting requests.

Some developers took the lack of code as an opportunity to argue that there was nothing to prevent them from building these new tall structures. The result was an onslaught of moratoria against the development of towers across the country, which in turn resulted in increased levels of litigation.

It was an understandable situation. Investors had just paid billions of dollars for wireless spectrum and were in a race to develop their networks in what was forecasted to be a booming industry. Newly incorporated, mobile operators were in a hurry, and it was reasonable for local planners and commissions to want to preserve the aesthetics and beauty of their communities. Nimbies began to attend zoning hearings by the busload.

NIMFY

Twenty years later, wireless history is about to repeat itself. The only difference is that instead of 200’ masts and rooftop mounts, we are deploying suitcase-sized boxes and small domes on light poles in the public right-of-way. People who live in suburban or dense urban neighborhoods may return from work one afternoon to find the latest technology deployed next to their driveway or just outside the window of their second-story bedroom in an apartment or townhouse – or said another way, in their front yard.

If we are not careful, we are going to create an entirely new movement of social media empowered people with the battle cry of “NIMFY!” and this will result in another wave of moratoria and legal battles.

The wireless industry has been placed in a difficult position. Consumers demand 24/7 high‑definition video streaming and reliable download/upload capability in their homes, at their offices, and while on-the-go in coffee shops, malls, and waiting in line – everywhere and any time. People get frustrated when they can’t get a signal on their phone, emails don’t send, or social media updates fail to post.

This is the generation of the cord-cutters: people who proudly renounce landlines and/or cable and rely on wireless connectivity instead. However, high volume of wireless use requires dense wireless infrastructure solutions. It’s a simple matter of math and science. Large macro-site towers serving large geographic areas no longer have the capacity to meet current consumer data use. Homeowners have spent hundreds of dollars on in-home signal boosters, only to find themselves pulling over on the drive home to complete a call because there is still no signal at the house.

The practical reality is that we need wireless facilities located closer to the high-volume user. Ironically, it’s the mobile user, not the carrier, who is driving wireless installations into residential areas. Rest assured that carriers do not spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to design and install a facility that is not needed by the customers. These small cell facilities are low‑powered and serve only that specific neighborhood. Cell sites are coming into residential neighborhoods because that is where the high-volume data usage is.

Right-of-way installations are not new. In fact, the carriers have a federal right to use public right‑of‑way without discrimination.[1] Carriers obtain encroachment permits or franchise agreements (similar to the franchise agreements given to public utilities or cable companies) from the local municipality to use the public streets. Wireless carriers are often certified by the state public utility commission.

DAS and small cell attachments are found on utility poles, traffic signals, and street lights throughout the United States. Right-of-way installations have been the solution to preserve coastal lines and provide an alternative to contested macro-site tower proposals. There are many outdoor small cell and DAS deployments that are installed without heartburn to the public or city planners. In fact, many jurisdictions require no zoning review for right‑of‑way attachments.

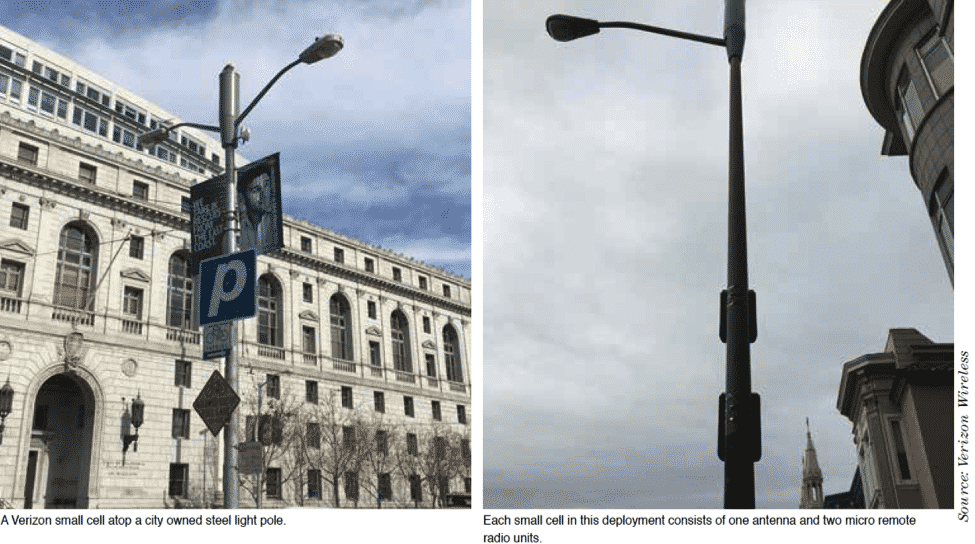

DAS and small cells can provide a win-win for the carrier and the public. For example, Verizon Wireless worked with the City of San Francisco to create a plan for the deployment of 400 small cells that balanced the carrier’s desire to more effectively meet current and future consumer needs with the preservation of the unique beauty and character that defines San Francisco as a world-class travel destination filled with historic sites and famous architecture. The examples below depict elegant small cell deployments.

But, where an installation is deployed directly in front of a residence without notice or a visually obtrusive installation is located outside a historic building, public opposition may potentially arise. In the 1990’s, the first-movers sometimes scorched the earth with unsightly tower deployments, burning bridges with the public and city planners for the carriers that followed. We hear reports that a similar approach may be underway with right-of-way installations. That method does not work in a 21st century society. In an era of social media and the internet, wireless facility installations do not go unnoticed. The internet and social media, the very reason why the facilities are installed in the first place, provide a conduit for information and complaints to proliferate. As a result, carriers are voluntarily and involuntarily relocating controversial pole installations.

PRACTICAL SOLUTIONS ARE NEEDED

The demand for 5G will only increase the need for densified networks in high‑volume urban areas. Wireless carriers need a stable, predictable environment in which they can efficiently deploy DAS and small cells within the right-of-way in a timely and cost-effective manner. Addressing public opposition and, worse yet, incurring the costs of relocation, diverts precious time, resources and money that a carrier would be better served investing in additional network infrastructure enhancements.

So, what do we do about it?

The following are a handful of lessons[1] we (should have) from the late 1990’s and (hopefully) won’t repeat in the late 2010’s.

FOR THE WIRELESS INDUSTRY:

1. Understand the environment surrounding the site. When designing a site, consider the look and feel of the location. For example, the installation of a new pole support structure or larger installation may meet opposition in an area with underground utilities or in residential neighborhoods. In contrast, that same design may be appropriate for industrial areas or urban thoroughfares proliferated by other street furniture, such as kiosks, cabinets, traffic signals, news racks, trolley poles, and street lights.

Also, familiarize yourself with any prior community concerns (if any) relating to cell sites. Even where community meetings or notices are not required by law, these may help smooth the overall process and encourage community acceptance of the site. Many of our clients have excellent materials designed to educate the general public. Take advantage of these resources. T-Mobile’s How Mobile Works website uses easy to follow graphics and straight-forward explanations to illustrate the interaction between larger tower sites and their smaller counterparts, the conditions under which a small cell system or DAS may be needed, and the benefits to the consumer (improved coverage and network speed) and the general public (improved 911 accessibility and caller location and identification services).

2. Silence in the code isn’t necessarily a green light. Carriers and tower companies should not assume that just because a local zoning code is silent on right-of-way wireless installations, this is the equivalent of a green-light to install whatever you want, wherever you want. Unless industry deployments are responsible and reasonable, a municipality may react by imposing a moratorium and developing onerous deployment requirements for future installations.

Given the opportunity, carriers can act responsibly and reasonably. Take, for example, backup generators. The federal government has explored the idea of regulating and mandating the installation of generators at cell sites to protect public safety and welfare in the event of a natural (or other) disaster. The wireless industry responded by voluntarily rolling-out back-up emergency generators at their sites. The carriers have also voluntarily implemented 911 wireless location capabilities far in excess of current Federal Communication Commission requirements.[1] As an industry, we do not need government intervention to make common-sense decisions.

3. Earning the municipality’s trust and respect will allow you to be an ambassador for positive changes. In recent months, the Md7 team has been working on a small cell polygon located in a burgeoning suburb in the Pacific Northwest. This particular municipality had never encountered the zoning approval of a small cell. Faced with a 30-node polygon, the jurisdiction initially requested we submit 30 separate zoning applications, each with a $5,000 deposit. After lengthy discussions with the jurisdiction, the planning department agreed to consider the polygon as a single system, reducing the number of applications from 30 to 1. This approach makes practical sense for both parties. Neither the jurisdictions nor the carriers can afford the time and money expended in treating a small cell node in the same manner as a cell tower. But change requires trust, which is often hard to earn and is easily lost.

Site acquisition and wireless industry professionals must be trained to effectively communicate to the municipality that expedited deployments support and further the interests of the community. Relevant factors may include: wireless service issues within the city, homebuyer preferences towards connectivity, and the symbiosis between the proposed small cell deployment and the municipality’s general or comprehensive plan.[2] Once an agreement is developed with the municipality, stick to the plan. If, for some reason, changes in the field necessitate a different direction, communicate with the jurisdiction early and often. Where mistakes are made, fix them quickly.

WHAT WE ASK FROM THE JURISDICTIONS:

1. Identify and communicate relevant concerns. To the extent that a jurisdiction has concerns regarding small cells and DAS installations within the right‑of‑way, it should issue clear standards that preserve the governmental interests while balancing the infrastructure needs of the community. Examples of jurisdictions that have already addressed right-of-way installations include Portland, Oregon; San Carlos, California; and Alpharetta, Georgia. And, even where we may not agree with the jurisdictional process or requirements, clear communication of the relevant requirements helps us submit complete and accurate application packages.

2. Make it easy to comply with local processes and requirements. Design requirements and approval processes should be easily available, preferably online. Consider email or online application submissions. Additionally, it is a pleasure to work with planning departments staffed with knowledgeable and easily accessible personnel.

3. Be prepared for volume. Municipalities should be prepared for the onslaught of applications for right-of-way installations. Nothing is more frustrating than hearing that the only planner that can review your application is on vacation or only comes into the office once a week. The much anticipated 5G mobile standard will only increase the number of siting applications being submitted. Inside Towers reports that Federal Communications Commission Chairman Tom Wheeler expects 5G’s infrastructure will rely heavily on small cells, towers, antennas and backhaul. Chairman Wheeler notes, “To make sure we have this connectivity with high-band spectrum will require a lot more small cells, which means a lot more antenna siting decisions by local governments.”[1]

To learn more about best practices for right-of-way deployments, click here.

HOW TO GET THERE

In the 1990’s, wireless connectivity was a luxury. Fast forward 20 years and wireless communication have moved from convenience to necessity. This utility has become essential to public health, safety, welfare, and happiness. Thus, while many not often realize it, the wireless industry and municipalities share a common goal of serving the greater public good. The same people that comprise the wireless customer base are also the government’s constituents. With that in mind, neither side can afford to repeat the mistakes of the past. We have much work to do.

In recognition of the essential nature of wireless service and the benefits it brings to the community, and in further recognition that there has been a long history of onerous and unwieldy siting processes in some jurisdictions, lawmakers at the federal, state and local levels have implemented or proposed regulations and legislation to help ease obstacles to deployment. With this ability to expedite deployments, the industry must ensure that it does not violate the trust placed in us by jurisdictions. We look forward to seeing more jurisdictions take a forward-thinking approach in investing in their communities by helping to bring wireless connectivity where it is most needed.

[1] 47 U.S.C. §§ 253(a) and 224(f)(1).

[2] Many of these lessons are taken from Best Practices for Deploying Wireless Infrastructure in the Public Right-of-Way, by Daniel Shaughnessy of Md7, available at: https://www.md7.com/2016/04/best-practices-for-deploying-wireless-infrastructure-in-the-public-right-of-way/

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enhanced_9-1-1

[4] See Best Practices for Deploying Wireless Infrastructure in the Public Right-of-Way, by Daniel Shaughnessy.

[5] https://insidetowers.com/cell-tower-news-new-5g-world-will-rely-on-familiar-infrastructure-fccs-wheeler/?utm_source=Inside+Towers+List&utm_campaign=29b7de2147-6_21_20166_20_2016&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_af16c4fc22-29b7de2147-66070353&goal=0_af16c4fc22-29b7de2147-66070353